Your browser is out of date, for the best web viewing experience visit Browse Happy to upgrade your browser today.

By Craig Dowley

There are a lot of questions about warehouse drones that we are often asked by customers and analysts. In particular, we have been asked about why, after performing automated inventory cycle counts at so many Fortune 500 warehouses for so many years, Vimaan is pivoting away from drones towards a different paradigm for automated cycle counting. So we thought it would be helpful to provide this tutorial article on the in’s and out’s of these novel inventory tracking devices – especially the challenges any drone solution would run into for automated cycle counting. Vimaan has flown more warehouse drone missions that any other solution provider in North America, making our team some of the most experienced domain matter experts in the world. We sat down with Sudhir Singh PhD, CTO of Vimaan who has extensive experience in the areas of computer vision and robotics to have him answer some of the most frequently asked questions on warehouse drones.

All sorts of industries have explored the use of warehouse drones to help solve commercial challenges. Several years ago, drones were first proposed to help improve the process of cycle counting in the warehouse. Cycle counting tasks have historically been very manual, time consuming, and prone to errors contributing to poor inventory accuracy within warehouses. The idea behind the use of warehouse drones was that they could fly around warehouse shelves capturing inventory data which would then be transmitted back to the warehouse system of record, thus providing a more up to date accounting of warehouse inventory, especially when it comes to high bay inventory scanning. Over the years the limitations of drones used for cycle counting have become more and more prevalent.

When most people learn of drones being used in warehouses, the first conjured image is that of drones carrying boxes around facilities — when in actuality, they are used primarily to help warehouses keep track of stored goods. Inventory accuracy is an important KPI for warehouses, and drones are used to fly through aisles taking pictures or scanning barcodes to inform the current status of stored goods. This data is typically transmitted through some middle layer to support discrepancy reporting against the warehouse system of record. However, these cycle counting missions are limited in duration due to very short battery life and a few other environmental challenges.

Today’s warehouses are more vertical than ever, and the fact that warehouse drones can easily fly to the highest warehouse shelves makes them a potentially safer alternative to warehouse workers being lifted over 30 feet in the air to capture inventory data. Another benefit was that instead of using labor to walk warehouse aisles documenting goods with scan guns (or sometimes with pen and paper), drones could be a cheaper and faster alternative to expensive labor. But that objective has not come to fruition due to high costs associated with deploying and managing warehouse drones.

That was one of the original objectives. Warehouses experience significant challenges with recruiting and retaining labor, and the goal was to have drones eliminate the need to backfill open positions and serve as a more reliable and cost-effective cycle counting option. Please see the response below for a cost and return analysis using drone expenses and warehouse labor costs.

The primary value proposition for drones is that they could backfill or replace existing cycle counting labor, allowing warehouse to redeploy available labor for other productive taskseliminate headcount salary. Some drone companies claim that they can deliver ROI in 12 months, but unfortunately the math does not add up. Warehouse drones are expensive technologies to deploy. Additionally the idea of eliminating cycle count workers is unrealistic, as warehouses still need workers to:

Warehouses using drones find that their cycle counters may spend less time auditing goods, but this time is quickly pre-occupied with the above tasks. Additionally, drones cost warehouses a minimum of $5-6K/month contributing to a very difficult path to ROI.

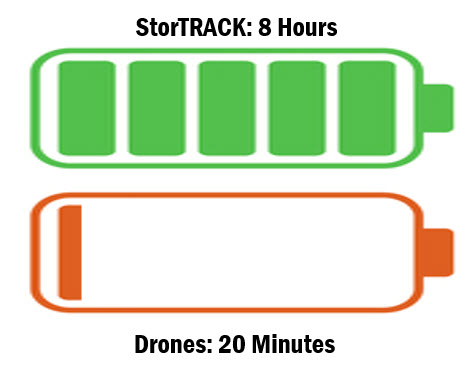

Regarding power retention, across the board, solution providers agree that drone batteries do not support more than 20 minutes of flight time. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean a drone spends 20 minutes scanning inventory; drones need to retain enough charge to safely return to their base station or they risk the chance of falling 30 feet to the hard warehouse floor. As a result, most drone missions are cut to 12-15 minutes of actual scanning. Once the drone returns for charging, it takes 60 minutes before it can depart again for another 12–15-minute mission.

It is of course possible to have charging stations situated at various locations around the warehouse so that the drone hops from one location to another without having to retrace its path and duplicate a scan, but this implies a large number of charging stations – which not only increases the solution cost but also creates logistical challenges in the warehouse of bringing power to the middle of the warehouse floor to multiple locations.

Many solution providers position their drones as “100% autonomous”. Unfortunately, this is not completely accurate for a few different reasons. The idea that drones run on their own while collecting inventory data sounds tempting, but warehouses that invest in drones quickly discover the harsh truth that drones introduce new challenges that require labor intervention and support. For example:

The label “autonomous” implies that a drone can operate independently without manual intervention or support. As detailed above there are many worker tasks required to keep drones operating. Workers that were previously assigned to cycle counting tasks are later reassigned to continuously clear aisles, clean shelves, and change batteries (every 20 minutes). This is just one of the many reasons why drones will never be a component of the “lights out warehouse”.

Not very reliably and in many cases NO. Very Narrow Ailes (VNAs) are typically designed to maximize storage efficiency by having narrow aisles that are only wide enough for specialized equipment to operate. Warehouse drones, particularly have difficulties nagiating these tight aisles due to their need for extra space to precisely maneuver around the racks.

As mentioned, it is very common for drones to come into contact with typical, everyday “hazards” of the warehouse like plastic, shrink wrap, tape, racks, paper, and more. When this happens more than half the time the drone will fall onto a shelf or on to the hard warehouse floor. When it falls on to a shelf it can go missing if someone wasn’t keeping an eye on it. When drones fall to the ground there is always the concern that it may fall on top of a worker. Drones operate on lithium-ion batteries, and by themselves they are not unnecessarily dangerous, but when they fall violently to the ground this could trigger an explosive event that could spark a fire and or damage goods. Other drone components like the camera and lights are also subject to damage any time a drone crashes.

Warehouse drones have become the badge of honor for warehouses that want to demonstrate their innovativeness to the rest of the industry. There is undoubtedly something cool about using drones to automate data collection. But now there is a much more reliable solution unimpacted by the drawbacks of drones listed above. The all-new StorTRACK from Vimaan is actively decommissioning drones in warehouses across the country.

Learn more about warehouse drones here:

Introduction to Warehouse Drones

For more information on warehouse drones, cycle count automation or StorTRACK, please feel free to contact our Customer Solutions Engineering Team.

This all-inclusive automation resource kit includes:

– Cycle Count Automation Demo Videos

– Real-world case study results

– Comprehensive automation guide

– Technology benchmark videos

– Product data sheets and specifications

– Sarbanes-Oxley compliancy technical note

– And more!